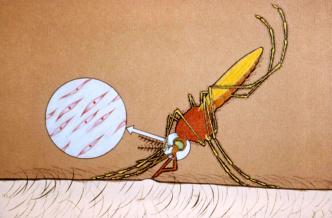

Rockefeller philanthropies promoted coordinated attempts to control or eliminate malaria in the 20th century by attacking the mosquito vector using insecticides such as DDT.

Malaria was identified as a specific disease in the latter 1880s and became the object of coordinated attempts to control or eliminate it in the 20th century. However, it remains endemic in tropical regions across the globe and is intertwined with socioeconomic conditions, particularly affecting the poverty-stricken and those with little or no access to health care.

Until the mid-1880s, malaria was relatively inseparable from various other fevers, particularly epidemic fevers that struck in the summers in both tropical and temperate zones. For example, the famous yellow fever epidemic that in 1793 struck Philadelphia, then the capital of the new United States, and killed about 10% of the population, probably had both malaria and yellow fever victims, although the deaths of the latter were far more dramatic and more frequent.

This understanding (or lack of understanding) changed in 1880 when Alphonse Laveran recognized the malaria parasite in the blood of infected persons. Giovanni Battista Grassi did research that in 1898 recognized particular mosquito species as carriers of the malaria parasite. At virtually the same time, Ronald Ross demonstrated conclusively that there was a malaria pathway between humans and mosquitoes.

The very fact that these milestones were accomplished by a Frenchman, an Italian, and a British subject working in India shows both the internationality of concern about malaria and that the tools of modern science could be brought to bear on disease research almost anywhere on the globe.

The potential foundation for malaria control developed in the mid-19th century with the fruitful intersection of scientific and investigative medicine. As the germ theory of disease origin and transmission took hold, new possibilities for understanding and controlling diseases emerged. Vector-carried diseases such as malaria, in which a living organism transmits an infection from one host to another, were more complex matters than human-to-human diseases, but they were also susceptible to new scientific-medical tools of analysis.

After Pasteur created his rabies vaccine, there was initially hope that science could produce a vaccine for malaria. However, unlike several other major diseases of mankind that were attacked and vanquished within a few decades after Pasteur’s invention, malaria did not prove susceptible to control by inoculation.

Early malaria control focused on treatment of infected persons. Until the 1930s, only quinine, derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree of South America, whose curative properties were known in pre-Columbian times, provided a consistent drug-based means of controlling the disease for those already infected. Early in the 20th century, the systematic distribution of quinine in some areas of the world allowed the malaria-infected to carry out life tasks without suffering malaria’s debilitating symptoms.

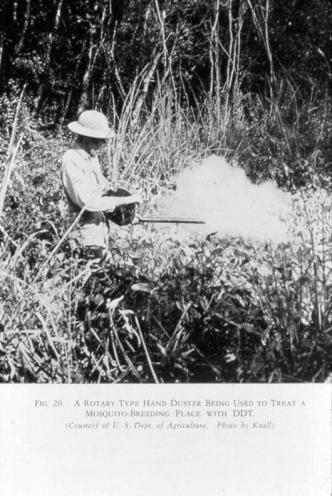

However, in the early 20th century, interest grew in attacking the source of malaria, mosquitoes. Such environmental strategies included screening windows, covering devices which collected water, and draining swamps. Later additions to such environmental strategies included controlled management of irrigation practices geared towards interrupting the propagation of mosquito larvae and introducing mosquito larvae-eating fish gambusias, which are sometimes called the mosquitofish for this reason. Most of these measures, which attempted to limit or stop the transmission of malaria by reducing the mosquito population, required constant vigilance.

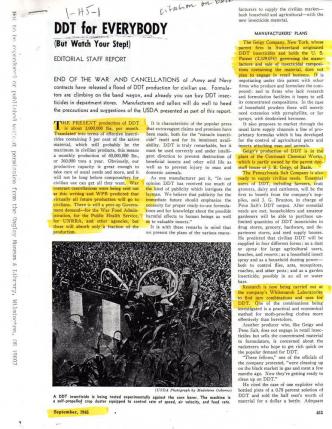

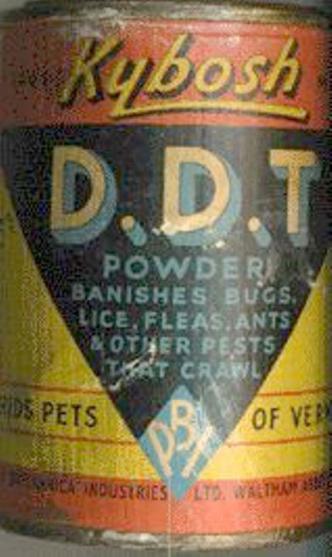

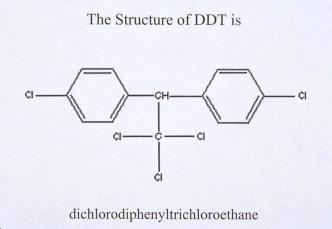

Nonetheless, by the end of the 1930s, global malaria control remained a vision that was far from realization. It was the advent of DDT – a powerful new insecticide – during World War II that created unanticipated possibilities. The story of DDT begins with the threat of another disease transferred by animals: typhus.

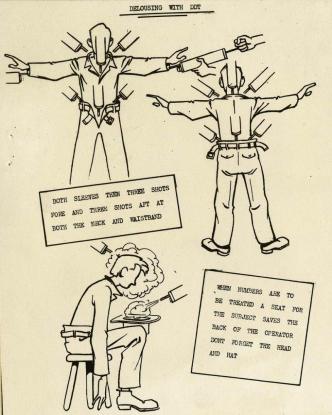

At the outbreak of World War II, public health officials had every reason to anticipate that major typhus epidemics would occur. As typhus is transmitted by the human body louse, the best means of controlling typhus epidemics at that time remained strict personal sanitation.

The alternatives at the time were the use of insecticides and vaccines, but the insecticides most effective against lice were in general highly toxic to humans. Moreover, the vaccines available were still in trial or untested in potential epidemic circumstances.

With the increasing likelihood of the entry of the United States into the war, typhus research grew into a significant element of the Rockefeller Foundation’s public health program. Because of the Foundation’s extensive connections, it could survey, study, and otherwise learn about typhus virtually throughout the world.

When typhus vaccinations proved disappointing, the Foundation created a laboratory for the study of the louse-borne typhus as a unit of the Foundation’s research laboratory located on the campus of the Rockefeller Institute in New York City. The Foundation’s antityphus laboratory was affectionately referred to as the “louse lab.”

However, the Foundation’s antityphus program soon was radically altered by the identification of DDT as a powerful insecticide that could control the human body louse, and soon they created an effective insecticide-delivery methodology based on DDT.

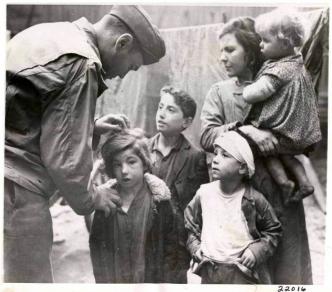

Their methodology was put to the test during an incipient typhus epidemic in Naples soon after the Allied invasion of Italy. The Rockefeller team from North Africa was called in and formed the backbone of the intensive project that eventually dusted 1.3 million people with insecticides. This event has generally been recognized by historians as the first clear demonstration of the control of human disease by DDT.

Rockefeller philanthropic institutions began tackling the challenge of malaria control in 1915, starting with the International Health Board. It first began experimenting with strategies for malaria control in rural areas of the southeastern United States and then expanded its experiments to other regions where malaria was common.

At the time, governments tended to favor ameliorative measures, such as providing quinine for those already infected. However, Rockefeller philanthropies believed strongly in taking preventative measures, using insecticides against mosquitos, thereby breaking, or attempting to break, the malaria transmission cycle.

The best-known and most visible Rockefeller anti-malaria activity was in Italy, beginning in 1924. After identifying the malaria-carrying mosquitoes specific to Italy and after studying the favored environments of those mosquitos, Lewis Hackett, the Rockefeller officer in charge there, centered his work on spraying mosquito habitats with Paris Green, a highly toxic double salt of copper and arsenic that had been identified recently as a mosquito larva killer. The ten-year Rockefeller program in Italy influenced a generation of public health workers around the world, many of whom visited the program’s demonstration site.

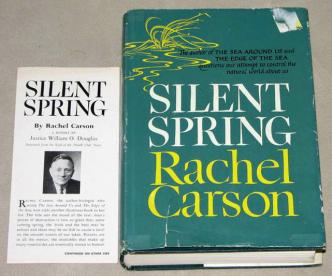

After the discovery of DDT and its effectiveness as an insecticide, the Rockefeller Foundation decided to attempt the eradication of mosquitoes from the entire island of Sardinia, a demonstration project that it carried out from 1946 to 1951.

The Rockefeller Foundation created a highly organized team that sought to locate and spray every breeding place of mosquitoes with the potential to carry malaria. In an area approximately the size of the state of New Hampshire, there were mountains, swamps, forests, villages, and small cities that had to be mapped, sampled, and efficiently sprayed with DDT. In the end, they managed to successfully eliminate the scourge of malaria from the island.

The Rockefeller anti-malaria program of using insecticides as a preventative measure avoided the messy problems of the alternatives, including forcing people to take quinine, which had an extremely unpleasant taste, or of relocating them away from areas where malaria was rampant.

Although the Rockefeller philanthropies were interested in public health in China since the late 1910s, malaria did not become a focus until 1939 when a Rockefeller officer in Hong Kong in wrote a letter to the Foundation’s New York office recommending the initiation of a malaria studies program in south and central China where it was “a major health problem.” He noted that Red Cross reports from Chinese military hospitals in those regions suggested that as much as 30% of the cases were chronic malaria, and that “this disease rivals or exceeds the intestinal diseases as a cause of sickness and disability.”

F.C. Yen of the National Health Administration of China suggested that recent graduates and current students at Peking Union Medical College could be recruited for the antimalaria project. The project itself was staffed by L.C. Feng of PUMC’s Department of Parasitology, two other Chinese researchers, and several Chinese support staff. In the first months of the project, it was found that the local malaria consisted mostly of P. falciparum infections, and that the only mosquito vector of importance at all was A. minimus.

The program of studying malaria continued through 1943, with the addition of trials of Paris Green for mosquito larva control. In the trial district, there was considerable improvement in prevalence of malaria compared to other nearby regions. In 1946, the Rockefeller Foundation’s report made mention for the first time of the possibility of using DDT on a trial basis for malaria control in China. Scientific studies and training of health officers continued until 1949.

Although political events made it impossible to continue antimalaria efforts in China, the Rockefeller philanthropies began a process which would have resounding effects in the future as the strategy they developed became the basis for the World Health Organization’s program of the 1950s and 1960s. The Rockefeller philanthropies, their intrepid staff, and the thousands of workers throughout the world that they brought into the struggle against malaria accomplished a great deal, and a global health infrastructure was put in place whose legacy is still with us today.

Crosby, Molly Caldwell. 2006. The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic That Shaped Our History. New York, NY: Berkeley Books.

McCullough, David. 1977. The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Poser, Charles M. and George W. Bruyn. 1999. An Illustrated History of Malaria. New York, NY: Parthenon.

Rocco, Fiammetta. 2003. The Miraculous Fever-Tree: Malaria, Medicine and the Cure That Changed the World. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Rosen, George. 1993. A History of Public Health. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Russell, Edmund P. III. 1996. “‘Speaking of annihilation’: mobilizing for war against human and insect enemies, 1914-1945.” Journal of American History 82 (No. 4): 1505-1529.

Shen, T.H. 1970. The Sino-American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction: Twenty Years of Cooperation for Agricultural Development. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Slater, Leo. 2009. War and Disease: Biomedical Research on Malaria in the Twentieth Century. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Stapleton, Darwin H. 2014. “Connecting Philanthropy with Innovation: China in the First Half of the Twentieth Century.” In Philanthropy for Health in China, edited by Lincoln C. Chen, Anthony J. Saich, and Jennifer Ryan, 120-136. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Stapleton, Darwin H. 2009. “Historical Perspectives on Malaria: The Rockefeller Antimalaria Strategy in the 20th Century.” Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 76: 468-473.

Stapleton, Darwin H. 2009. “Malaria Eradication and the Technological Model: The Rockefeller Foundation and Public Health in East Asia.” In Disease, Colonialism, and the State: Malaria in Modern East Asian History, edited by Ka-che Yip, 71-84. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Stapleton, Darwin H. 2008. “Technological Solutions: The Rockefeller Foundation and the Insecticidal Approach to Malaria Control.” Paper presented at the conference “The Global Crisis of Malaria: Lessons of the Past and Future Prospects,” Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, November 7-9.

Stapleton, Darwin H. 2005. “A lost chapter in the early history of DDT: the development of anti-typhus technologies by the Rockefeller Foundation’s louse laboratory, 1942-1944.” Technology and Culture 46 (No. 3): 513-540.

Stapleton, Darwin H. 2000. “Internationalism and nationalism: the Rockefeller Foundation, public health, and malaria in Italy, 1923-1951.” Parassitologia 42 (No. 1-2):127-134.

Stapleton, Darwin H. 1998. “The dawn of DDT and its experimental use by the Rockefeller Foundation in Mexico, 1943-1952.” Parassitologia 40 (No. 1-2): 149-158.

Williams, Trevor I. 1982. A Short History of Twentieth-Century Technology, c. 1900-c. 1950. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

World Health Organization. 1958. The First Ten Years of the World Health Organization. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/a38153.pdf?ua=1.

World Health Organization. 1968. The Second Ten Years of the World Health Organization. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/14564.pdf?ua=1.