The development of the X-ray unit at PUMC is a history of the transfer of scientific instrumentation.

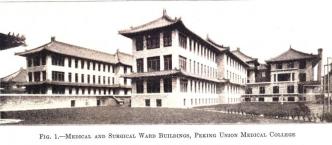

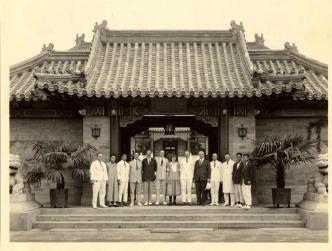

When Peking Union Medical College was formally inaugurated in 1921, it was known for being a first-rate modern biomedical research facility. When Donald Van Slyke, on loan from the Rockefeller Institute, spent a semester as a visiting professor at PUMC in the early 1920s, he carried out a landmark experiment on gases in the blood aided by “three superb Chinese technicians” and remarked that the excellent PUMC facilities allowed him to do in three months what might have required a year anywhere else.

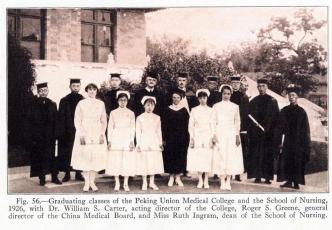

At that time, English became the language of instruction at PUMC because the faculty would initially be recruited from the United States, Canada, and Europe. This had the effect, intended or not, of limiting the pool of students to those who had been educated in English-language missionary schools or had been educated in North America or other Anglophone areas. Although the members of the Rockefeller Foundation and the China Medical Board had originally hoped that PUMC would be staffed completely by Chinese scientists within a generation, it ended up taking two generations to complete that goal.

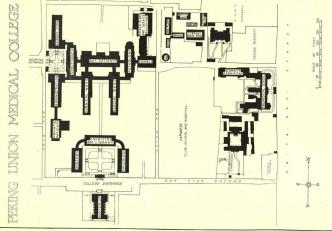

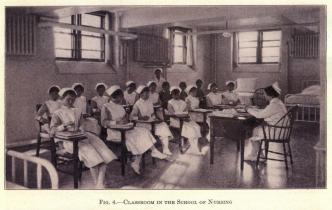

PUMC’s educational programs included a pre-medical unit for providing promising students with sped-up scientific training, a medical degree program, and a nursing program. All of these programs turned out a small number of graduates, but these medical and nursing graduates quickly moved into leadership positions or teaching positions at PUMC and other institutions in China. Another key part of PUMC’s educational system was the transfer of new scientific instrumentation.

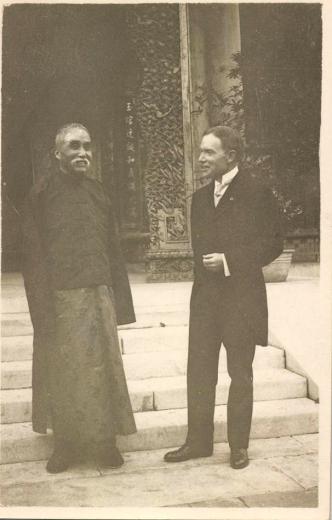

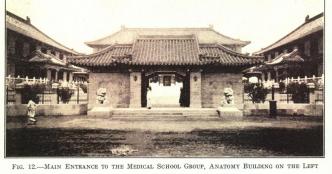

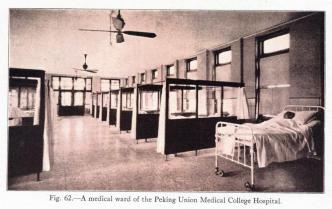

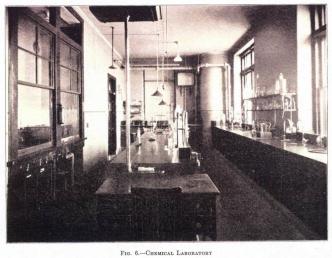

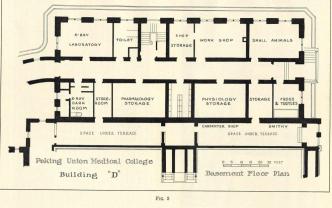

PUMC’s research departments included anatomy, chemistry, physiology, and pathology. The college had a fully functioning hospital, and, in order to provide opportunities for research on human subjects, it generally only took in patients whose diseases were of interest. One great exception to this rule was the admission of China’s president, Dr. Sun Yat-sen, early in 1925 for evaluation during the course of his final illness.

Between PUMC’s educational programs, the facilities providing opportunities for modern biomedical research, and an accompanying fellowship program allowing Chinese students to study in the U.S., PUMC provided a modern education for an emerging generation of Chinese doctors and scientists. As Mary Brown Bullock has stated in her history of PUMC:

“…PUMC students were taught even the most fundamental subjects by experts in their fields… Not only were these men internationally-acclaimed medical scientists, they continued their own pioneering research… within the laboratories of PUMC.”

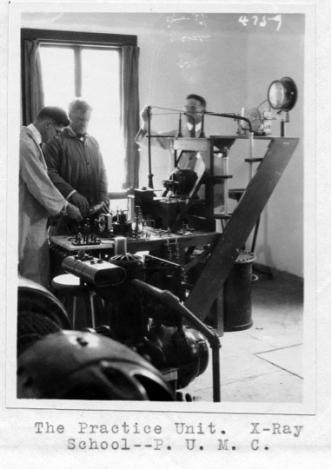

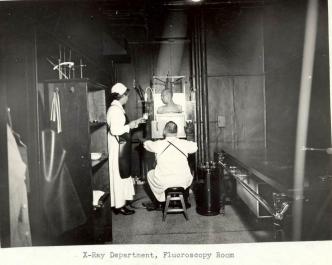

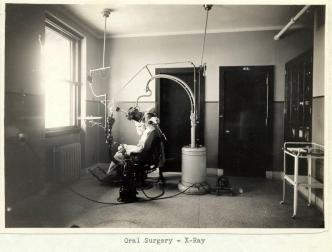

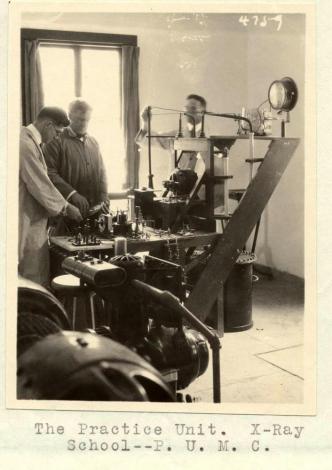

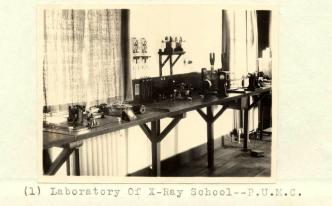

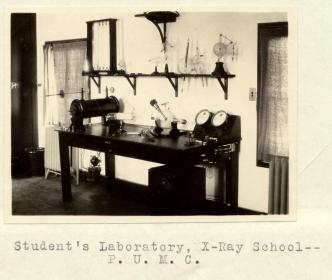

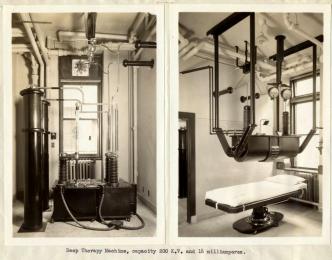

Today, what we would call the radiology department or X-ray department was originally called the Roentgenology Department, due to W.K. Roentgen’s discovery of X-ray technology in 1896. X-ray technology developed rapidly in the early twentieth century, becoming both a tool for scientific investigation and a valuable addition to the diagnostic capabilities of medicine. The development of the Roentgenology unit at PUMC provides an excellent example of the transfer of scientific instrumentation into China.

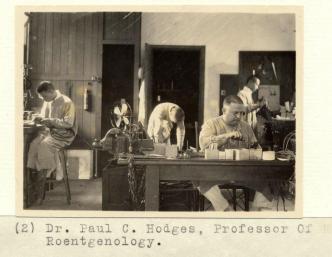

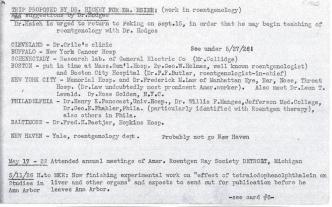

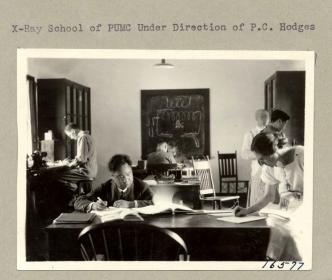

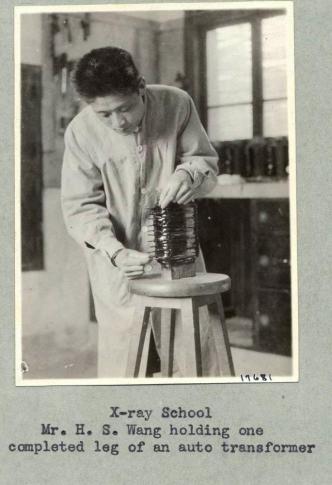

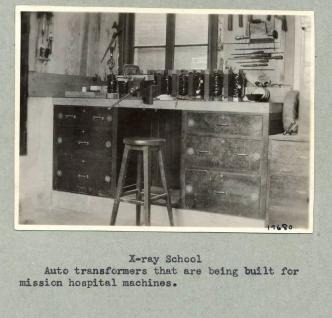

The Roentgenology unit at PUMC was headed by Paul C. Hodges, who was, according to one historian, “a recognized master of radiological instrumentation.” His mastery made the Roentgenology unit one of the most active teaching centers at PUMC, and with grants from the China Medical Board, he also helped create a new line of inexpensive, portable X-ray devices which were produced in China with a small number of imported materials, and which enabled the spread of X-ray technology to various universities and hospitals throughout China.

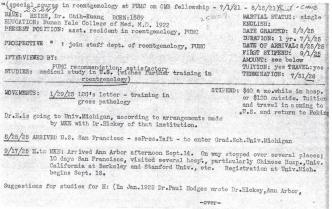

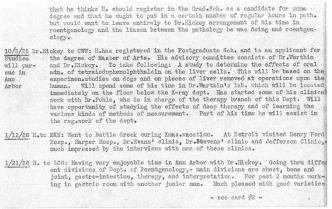

Under Hodges’s lead, the Roentgenology unit was one of the first places at PUMC to make a commitment to Chinese leadership. Hodges identified Hseih Chih-kuang as a potential future leader in medicine. Hseih studied abroad in America, thanks to a fellowship granted by CMB, and he eventually obtained his master’s degree in Roengenology from the University of Michigan. In 1928, he became the head of PUMC’s Roentgenology unit, and he served in the position for twenty years.

Fang Hsien-chih, a PUMC graduate of 1933, would later follow in Hseih Chih-kuang’s footsteps and, in the mid-1950s, became head of the radiology department at the renamed PUMC, the China Union Medical College. From this, we can see the continuous transfer of knowledge from generation to generation.

The Roentgenology unit at PUMC demonstrates all the major processes of technological transfer. Original knowledge and equipment came from a nation with advanced knowledge. Up-to-date training was provided to an individual from a nation lacking that knowledge. Lastly, the manufacture of the technology in the new nation finalized the transfer of technology.

Bowers, John Z. 1972. Western Medicine in a Chinese Palace: Peking Union Medical College, 1917-1951. Philadelphia: Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation.

Bullock, Mary Brown. 1980. An American Transplant: The Rockefeller Foundation and Peking Union Medical College. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Chen, Kaiyi. 1996. “Missionaries and the Early Development of Nursing in China.” Nursing History Review 4: 129-149.

Richtmyer, F.K. 1931. “X-rays and Their Uses.” The Scientific Monthly 32 (Issue 5): 454-457.

Richtmyer, F.K. 1926. “‘Seeing’ with X-rays.” The Scientific Monthly 22 (Issue 6): 550-554.

Röntgen, W.K. 1896. “A New Form of Radiation.” Science 3 (No. 72): 726-729.