Part 3 of a three part series on the history of Rockfeller engagement and the development of public health in Sri Lanka.

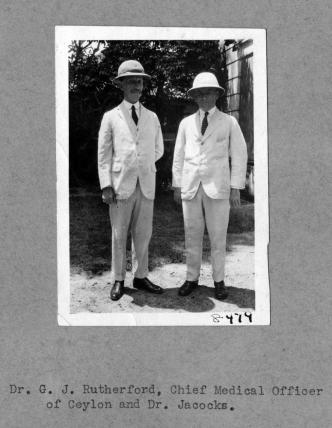

William P. Jacocks (1877-1965) was a doctor of public health. Jacocks’ early experience in the American South as a public health officer of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission enabled him to study the concept behind health units, which focused on gathering vital statistics, analyzing epidemiological data, promoting health education, and developing health promotion activities. Jacocks used these early experiences in America to help develop the Rockefeller Foundation’s public health program in Sri Lanka.

Jacocks coordinated the Rockefeller Foundation’s public health programs for almost two decades, working closely with his counterparts in Sri Lanka to develop essential health services and train local public health personnel for the health unit program. It was largely due to Jacocks’s expertise and diplomatic skill that the health unit program succeeded there. Among his many accomplishments in this regard, Jacocks laid the groundwork to secure the Rockefeller Foundation’s support to develop a professional nursing education program in Sri Lanka.

In 1926, Jacocks undertook a study to access the needs of public health personnel in Sri Lanka and found that there were no public health nurses in the country. The public health nurse was an essential position in the health unit program, and in 1928, there were five health units, with two more on the way, none of which had public health nurses.

In 1928, the government began training public health nurses at the Kalutara health unit. When the position of public health nurses was first created, it was decided that only unmarried women with nursing backgrounds should be selected. It was believed that they would not require a long period of training, and they would be free of personal responsibilities, such as family, in the beginning of their careers. However, these hospital nurses preferred hospital jobs to fieldwork and felt they were undercompensated financially for their efforts. For these reasons, the program failed to retain many new recruits. It was becoming clear that the government would need a new policy to attract qualified recruits.

Understanding this, Dr. Rupert Briercliffe, Director of the Department of Medical and Sanitary Services in Sri Lanka, devised an interim solution. Briercliffe decided to recruit married women, who had been trained in hospital nursing, but had resigned from the service after getting married. He decided to re-train them in midwifery and in public health nursing for a period of one year before employing them in the health units. This solution proved successful in the short-run, but a long-term fix was still needed.

In order to attract qualified candidates and increase recruitment, the government created a junior grade of female health workers, which better compensated employees for their education and hard work. Each junior health worker underwent training in midwifery, followed by 12 months of training in public health nursing at the Kalutara health unit and the local hospitals. The training focused on many aspects of maternal and child welfare work, including nutrition, vaccination against infectious diseases, administering treatment for hookworm infections and malaria, and conducting health education seminars for school children.

While the creation of this position was not exactly the solution Jacocks had wanted, he was pleased at the government’s response. The creation of junior health workers helped to solidify the position of the health units, so they could continue to successfully provide public health services in Sri Lanka and serve as a model for health units throughout Asia.

Hewa, Soma. 2014. "Introducing Modern Nursing to Sri Lanka: Rockefeller Foundation and Colombo School of Nursing." Galle Medical Journal 19 (No. 1): 17-22.

Hewa, Soma. 2011. "British Colonial Politics and Public Health: the Rockefeller Foundation's Effort to Develop Public Health Nursing in Sri Lanka." Galle Medical Journal 17 (No. 2): 27-31.