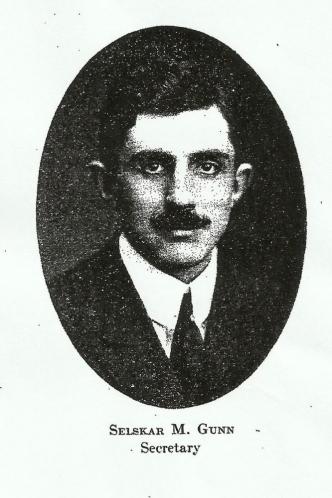

Selskar Gunn, a Vice President of the Rockefeller Foundation, started a rural reconstruction project in Northern China with the goal of meeting all the needs of local communities there.

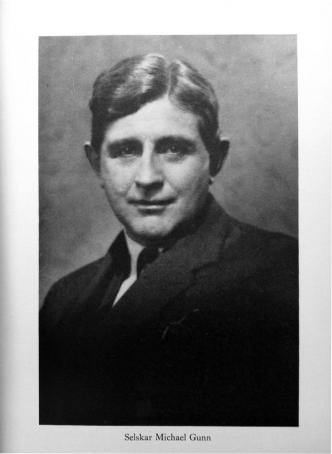

Selskar Gunn had an unusually varied career. He worked as a health officer in New Jersey, an editor of the American Journal of Public Health, a teacher of public health, and Director of the Massachusetts Division of Hygiene, which he helped design. While living in Europe and working for the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation, Gunn came into contact with Andrija Štampar, an influential thinker and distinguished scholar of social medicine.

Gunn’s intellectual development was deeply influenced by Štampar’s ideas, which emphasized the importance of agriculture and education for public health. Gunn had been working with Štampar in developing an ground-breaking program in Yugoslavia, which would bring together such disparate fields as education, economics, sociology, engineering and agriculture, with the eventual aim of developing a form of rural government which would take into consideration all the social needs of the community.

Though a program of rural reconstruction in Yugoslavia failed to materialize for political reasons, Gunn took Štampar’s ideas to heart. Gunn believed that improving the welfare of mankind, the stated goal of the Rockefeller Foundation, could be more effectively demonstrated through a multi-sectoral approach than each discipline undertaking a single subject in isolation.

With the prospect of creating such a program in Europe fading, Gunn turned his attention to other parts of the world, searching for an appropriate place to put his ideas into practice. In the summer of 1931, Gunn, by then a Vice President of the Rockefeller Foundation, visited China for the first time. After spending several weeks visiting a variety of educational, medical, and governmental institutions in China, including Jimmy Yen’s innovative demonstration center at Dingxian, Gunn began to believe that China could be an ideal place for the implementation of his and Štampar’s ideas.

Raymond B. Fosdick once provocatively asked: “Are we to have two techniques in public health – one for the rest of the world and one for China?” Despite some misgivings concerning the relationship of the program to the rest of the Foundation’s activities, the Board of Trustees endorsed Selskar Gunn’s program for rural reconstruction in China, and one million dollars were appropriated for a three-year experimental program which begun in July 1935.

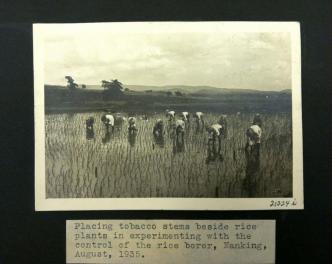

The program was multidisciplinary in nature, and its aim was to raise the educational, social, and economic standards of rural China to improve health. It was recognized by some at the time as an alternative to the International Health Division’s approach to public health, which focused its efforts on how to best control and, if possible, eradicate specific infectious diseases.

Selskar Gunn worked closely with Peking Union Medical College professor, John Grant, to implement the program. Grant focused on introducing preventative medicine into the curriculum of PUMC and strengthening the national government’s capacity to develop a national health system. Grant was instrumental in the execution of the rural reconstruction program and can be considered almost as much the author of the rural reconstruction program as Gunn.

In developing the program, Gunn and Grant discovered a mechanism to ensure that no critical discipline would be overlooked was missing. In order to coordinate the work of such disparate fields as economics, public affairs, agriculture, and education, they established the North China Council for Rural Reconstruction, which brought together officials from Nankai University, Yenching University, the National Agricultural Research Bureau, Jimmy Yen’s Mass Education Movement, and Peking Union Medical University.

The program in the end, however, would be short-lived. While the invasion by Japan in 1937 did not lead to the immediate closing of Gunn’s program, the disruption that it caused made planning for the future almost impossible. Who’s to say what the program, which started with such enormous potential, would have accomplished had it continued?

Bullock, Mary Brown. 1980. An American Transplant: The Rockefeller Foundation and Peking Union Medical College. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

“China.” 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation. http://rockefeller100.org/exhibits/show/agriculture/china.

Farley, John. 2004. To Cast Out Disease: A History of the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation (1913-1951). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Litsios, Socrates. 2014. “The Origin of PHC: Some leading names and major events 1928-1974.” World Health Organization: Lunchtime Seminars Series 2014. http://www.who.int/global_health_histories/seminars/2014/en/.

Litsios, Socrates. 2009. “The Rockefeller Foundation’s Struggle to Correlate Its Existing Medical Program with Public Health Work in China.” In Uneasy Encounters: The Politics of Medicine and Health in China 1900-1937, ed. by Iris Borowy, 177-203. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Litsios, Socrates. 2008. “Selskar ‘Mike’ Gunn and Public Health Reform in Europe.” In Of Medicine and Men: Biographies and Ideas in European Social Medicine between World Wars, ed. by Iris Borowy and Anne Hardy, 23-43. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Litsios, Socrates. 2005. “Selskar Gunn and China: The Rockefeller Foundation’s ‘Other’ Approach to Public Health.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79 (2): 295-318.

“Selskar M. Gunn.” 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation. http://rockefeller100.org/biography/show/selskar-m--gunn.

Thomson, James C., Jr. 1969. While China Faced West: American Reformers in Nationalist China, 1928-1937. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.